Our Club History

Brief History of Rotary Club of Louisville, Inc.

By: Anthony Newberry

110 Years of “Service Above Self”: A Short History of the Rotary Club of Louisville, 1912 – 2022

Based on the “Brief History of the Rotary Club of Louisville, Inc” By Martin Schmidt and William Brittain (2004)

Supplemented by the Work of Charles Harris, Joseph Lenihan, Patricia Cross, Rick Harned, Maynard “Stet” Stettin and other Rotary Historians

Rotary’s Beginnings in Louisville

In late 1911, three civic-minded Louisville businessmen, Truman McGill, C.H. Hamilton, and Frank B. Jones, read newspaper articles about the recent formation of a Rotary Club in Boston, Massachusetts. Impressed by Rotary’s commitment to high ethical standards, business networking and public service, the three wrote separate letters to Rotary headquarters in Chicago asking how such a Club might be established in Louisville.

Before their letters, McGill, Hamilton and Jones were unacquainted with one another. But soon, with encouragement from Rotary’s General Secretary Chesley Perry, the three met at Hamilton’s office in the Walker Building at 5th and Market to discuss the potential for a local Rotary Club. Hamilton was a commercial builder and general agent for the Sheldon School, Jones a representative for Burrough’s Adding Machine Company, and McGill a jeweler with L. Huber and Son. All three were attracted to the Rotary idea of fellowship and service among professionals from different lines of work. In short order, with encouragement from Rotary founder Paul Harris as well as General Secretary Perry, the three men developed a game plan and began to reach out to like-minded business leaders.

Over the spring and summer of 1912, Hamilton and McGill organized a series of eight working sessions devoted to drafting bylaws and a constitution and recruiting potential members. (Frank B. Jones had moved to Lexington in April to accept a new position.) The meetings occurred in downtown restaurants, most often at Klein’s or the new Hotel Henry Watterson, and typically included eight to fourteen other business leaders.

By May 17th, the still unofficial Rotarians elected a preliminary slate of officers, with Lawrence L. Anderson, a local insurance executive, as president, bank executive A.S. Rice as 1st vice president and C.H. Hamilton as secretary-treasurer. On June 15th Hamilton wrote the Chicago office to announce that “Louisville is in the ring!” and that member recruitment, a constitution and bylaws and plans to attend the national convention were well underway. On July 15 Anderson, Rice, Hamilton, McGill and 12 other businessmen completed the official membership application which Hamilton quickly mailed to Chicago. The official Charter arrived on July 24, and two days later, in an historic Charter Day meeting at the Watterson Hotel, the Rotary Club of Louisville became the 45th Club in the world with 38 original members.

The Louisville Club and the Early Expansion of Rotary

The Louisville Club was initially part of a district which embraced ten states. With the rapid establishment of new clubs throughout the nation, the district was reduced to four states in 1915 and in 1918 to the states of Kentucky and Tennessee. In 1925, by which time Rotary International had 2,000 clubs on six continents, Kentucky became a district by itself and continued that way until 1937 when the Commonwealth was divided into two districts. From that point forward, the Louisville Club has been part of a Rotary district which serves the western half of the state (today’s District 6710).

From the beginning, the Rotary Club of Louisville led the way in starting new clubs throughout Kentucky. It organized the Paducah and Lexington clubs in 1915, for example, and subsequently supported fledgling clubs in Lebanon, La Grange, Hodgenville, Henderson and Elizabethtown as well as New Albany, Indiana, Charleston, West Virginia and Knoxville, Tennessee. One Louisville Rotarian, Eugene Pendergrass, served as chairman of the District Extension Committee and had a hand in establishing several of the new clubs.

Acquaintanceship, Fellowship and “Community Betterment”

From its earliest years, the Rotary Club of Louisville emphasized acquaintanceship and fellowship alongside the larger goal of making the Louisville community a better place to live. The Club’s rapid growth, from 38 to 122 members in its first year, posed a serious challenge to building the mutually-beneficial business friendships envisioned by Rotary’s founders. In June 1913, the annual roster first included photos of every member, a point of pride for the Club’s Boost Committee charged with promoting fraternal spirit. In September the first issue of SPARKS, the Club’s bi-weekly bulletin, proclaimed President Frank Bush’s goal that “every Rotarian will know every other Rotarian, not only by face, but also by name and the business that goes with it.” Each issue of Sparks included sketches of members and their businesses; many meetings included “acquaintanceship pranks” designed to encourage networking across multiple professions.

When it came to “community betterment,” early Club leaders worried that Louisville misunderstood Rotary as just a self-interested “business swapping organization.” Yet a key object, embedded in the Club Constitution, was “to quicken the interest of each member in the public welfare and to co-operate with others in civic development.” The Constitution charged the Committee on Public Affairs with reporting to the membership on “matters affecting the public welfare” and devising and executing “plans for the upbuilding of the city of Louisville.”

In 1914, the Club addressed public misperception with a special Rotary Edition of the Louisville Herald which featured testimonials from national leaders and emphasized the commitment to improving the community. “This one issue of the Herald,” Club president Louis Webb remembered, “did more to put Rotary on its feet in Louisville than any other one thing.” The Club soon undertook ambitious service projects, including the movement to restore the burial place of Zachery Taylor and the creation of a student loan fund to support “worthy boys” of modest means at Male High School which opened at Brook and Breckinridge in 1914.

In the years before World War I, the Club’s involvement in public welfare initiatives also included fundraising for the Salvation Army and the YMCA and support for the city government’s fledgling efforts to assist the unemployed. But it was economic development that generated the most enthusiasm. The Club supported Louisville as the location of a Regional Federal Reserve Bank and the military encampment which became Camp Zachery Taylor, for example. It boosted efforts to create a permanent “Made in Louisville” Manufacturing Exhibit and passed a resolution in support of merging the Board of Trade and the Louisville Commercial Club, thereby combining the city’s industry recruitment efforts. The Club constitution prohibited political endorsements but after full discussion at the board and in meetings, the Club threw its support behind the $1 million school bond issue and the replacement of the county fiscal court with the county commission form of government.

Early on the Club also worked to establish itself as a premier platform for speakers. An example was the large gathering on December 30, 1915 on the Roof Garden of the Seelbach hotel where the featured speakers were Rotary International President Allen Albert and AT&T Vice President N.C. Kingsbury. The theme of the evening was the amazing “progress of telephone developments” in the United States. Club president Frank T. Buerck remembered that at “each chair of the nearly 500 guests was a receiver which enabled every one present to hear conversations between Louisville and the Pacific Coast, one of the first demonstrations of long distance telephone.”

The 1915 visit of RI President Albert reflected the Louisville Club’s extensive early collaboration with the fast-growing international Rotary organization. The Club sent delegations to every annual conference in these years. In June, 1916, when Cincinnati hosted the RI Convention, the Club’s newly formed Women of Rotary organization provided hospitality to hundreds of Rotarians en route to the Queen City, and the Louisville Club reserved an entire floor at the conference hotel.

Louisville’s Robinson “Bob” McDowell served as District Governor, then as First Vice President of Rotary International, and on RI’s behalf visited new clubs in Tennessee, Arkansas and Mississippi. At each stop McDowell spoke movingly about “the principles of Rotary, defining its spirit, telling of the aims and purposes of the clubs and individuals who composed them, and [stressing] that the spirit of Rotary is one of unselfishness; one of uplift; one of progress; one of building up, and . . . one of lending the helping hand and injecting a friendly spirit in competing businesses.”

These early efforts at community betterment had serious limitations, including the provisions in the Club Constitution which excluded non-whites and women from membership. Yet the commitment to “quicken the interest of each member in the public welfare” and “cooperat[e] with others in civic development” — along with Rotary International’s aggressive expansion to nations and cultures around the world — planted the seeds of a more inclusive, diversity-oriented vision, one that would emerge forcefully in the latter decades of the 20th century.

World War I and the Flu Epidemic of 1918-19

In 1917-18, as America became fully engaged in World War I, Club Minutes and newsletters contained multiple references to the war effort, from support for war gardens, sugar conservation and liberty bonds to Honor Rolls of Rotarians who served and in some cases died in service to the nation. As one Rotarian remembered it, meetings were “intensely patriotic” and speakers often included “distinguished American generals and military officers of England and France.” In late 1918, the Club passed resolutions in celebration of the victory in Europe and made plans to participate in the city-wide parade scheduled for November 23rd.

But the victory spirit faded as an unprecedented influenza epidemic spread across the region. Articles in Sparks announced that in “compliance with the spirit of the order of the Board of Health,” there would be “No Regular Meetings” from October 6 through November 11 and that “Many Rotarians and members of their families were stricken with the ‘flu.’” Club President Wade Sheltman, writing 20 years later, remembered there was “rarely a meeting of the Club when it did not stand in silent tribute to some member or the relative of a member who was a victim of this plague.”

The Optimistic 1920s

In the post-war years, Rotary members were increasingly prominent in major civic initiatives. In 1921, for example, Rotarians led by Henry Vogt participated in Mayor Huston Quin’s efforts to improve the city’s form of government. That same year the Club presented a resolution to the Board of Trade and the Board of Park Commissioners in support of the municipal airfield for Louisville. (Bowman Field was officially dedicated August 15, 1923 with commercial passenger service beginning in 1924.) In October 1922, when radio was in its infancy, the Club hosted a radio program on WHAS which focused on Rotary ideals and public affairs.

Since 1912, the Hotel Henry Watterson had been home to weekly meetings and starting in 1919 the Club’s administrative office, the latter a concession from Club member Robert B. Jones who managed the hotel. But in 1924, the Club moved its weekly meetings and office from the Watterson to the newly constructed Brown Hotel. At the 2nd meeting on January 10th, 387 members of the Louisville, New Albany and Jeffersonville Rotary Clubs gathered to hear speakers advocate for a new bridge across the Ohio River. In 1929, Rotarians on both sides of the Ohio River joined in celebrating the opening of the George Rogers Clark Memorial Bridge.

The Rotary Club of Louisville dramatically increased its “community betterment work” in the 1920s. In 1925, to cite one example, the Club hosted a meeting of the International Society for Crippled Children and played a key role in creating the Kentucky Chapter of the national organization. 251 of the club’s 253 members became dues paying members of the Kentucky Society, and the Club itself appropriated $1000 to equip two wards at Kosair Children’s Hospital. Several members served on the Kosair Board and as chairmen of local fund drives.

Throughout these decades, attendance at weekly meetings was a major focus of both Rotary International and the Louisville Club. The Club’s membership tripled in the first year from 38 to 122, then grew gradually to 225 on the eve of WWI. During the 1920s, membership ranged from a low of 233 and a high of 264. Average weekly attendance held steady around 76%, prompting the Louisville Club to issue attendance challenges to other large Clubs. In November 1924, for example, 228 of Louisville’s 248 members appeared on the appointed challenge day. Yet the Club lost in competition with the Nashville Club which had perfect attendance. It was not unusual in these years for more than half of the Louisville Club’s members to achieve 100% annual attendance. But 100% for the entire membership at a weekly meeting remained a Rotary president’s dream.

A key to attendance was a concerted effort to promote fellowship, camaraderie and member engagement. As Club historian Joseph Lenihan put it in 1987, “fun was no stranger to Rotary in its youth, perhaps a more frequent visitor than today, when we effect a certain dignity and take ourselves more seriously.” One example was Frolic Day, when forks and spoons disappeared from the place settings, upsetting the table manners of the most respectable Rotarian. Entertainment at interclub meetings sometimes included large scale pranks. An epic 1914 visit from the Evansville Club featured a staged boxing match and a mock police roundup. A dinner in honor of the Lexington Club in 1915 featured vaudeville stunts and an imitation funeral procession, the levity moderated at key moments by serious talks on the “Higher Principles and Ideals of Rotary” and the “Significance of National Highways”. Extreme hijinks subsided after World War I but for many decades election campaigns between slates of candidates for Club offices were “more strenuous than a hot national presidential election.” The most valued activities were undoubtedly the annual sporting events in golf, bowling and target shooting, as well as the Club-wide social gatherings during holiday times and summers.

Stock Market Crash, Depression and the Great Flood of 1937

The stock market crash of 1929 and the subsequent onset of the Great Depression seriously affected the Club, bringing a loss of membership, financial stress and a need to reduce expenses. One near casualty was Sparks, which moved from bi-weekly to weekly publication in 1927 and by 1929 encompassed 12 or more pages per issue. With the budget squeeze, leaders considered cancelling Sparks altogether but settled on a page reduction and a mandate that advertisements would cover all costs.

As the depression deepened, weekly speakers included a director of the Federal Reserve of St. Louis who warned that the “way out of the depression is not government interference with the law of supply and demand” and a presenter from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce on “Rotary’s Place in the Present Business Situation.” In 1931, the Club passed a stirring resolution of praise of former Mayor and current Club Vice President Huston Quin, who was instrumental in the reorganization and reopening of the Louisville Trust Company, whose closure in November 1930 had rocked the business community. In July 1933, in response to an encouraging speech about President Franklin Roosevelt’s rescue plans, the Club suspended its rules to issue a unanimous resolution of support for the recently enacted National Industrial Recovery Act.

In the early 1930s the Club intensified its focus on underprivileged youth, including a new fund to support lunch fees for children in the public schools, a campaign to boost support for the Children’s Hospital, and involvement in the Community Chest (the forerunner of Metro United Way). The Club threw itself into the work of the Boy’s Work Council of Louisville, advocating for supervised city-wide playground activities for all children. The Club also supported the Otter Creek Commission’s plans to establish the YMCA’s Camp Piomingo in Brandenburg. Dozens of Rotarians supported the “back to school” movement, working one-on-one with students who had informed their principals of plans to leave high school. Encouragement and persuasion were the main tools. But when family finances were the issue, Rotarians provided students with part-time jobs.

The Great Flood of January 1937 had a major impact on all the Rotary Clubs in cities and towns along the Ohio River. In Louisville, the flood brought three feet of water onto the ground floor of the Brown Hotel and forced the cancellation of several meetings. The devastation also spurred the Club to work with volunteer groups and local government to tackle the massive problems of clean-up and repair. In July 1939, when heavy rainfall brought flooding to Morehead, Jackson and other mountain communities, the Louisville Club sent aid to Eastern Kentucky.

By the time of the Rotary Club of Louisville’s Silver Anniversary celebration on October 14, 1937, there were 60 clubs in Kentucky and 4,720 in 80 countries around the world. Club leaders read a handwritten letter from Rotary founder Paul Harris praising “the achievements of the Rotary Club of Louisville” and the “sacrificial efforts” and “high purpose” of the membership. RI’s General Secretary Chesley Perry added his congratulations, reminiscing about his correspondence with C.H. Hamilton, Truman McGill and other “founders of the club” who “had a vision, accepted the challenge it offered, and had the courage to persist in spite of criticism and discouragement.” The Club had come a long way since those fledgling years and had now established itself as a force for community betterment and “service above self” in Louisville.

World War II, the Post-War Years and the 1950s

When World War broke out in Europe in September 1939, the Rotary Club of Louisville’s weekly meetings hosted speakers on multiple aspects of the widening conflict, not only in Europe but in the Far East. In 1940 and 1941, several speakers addressed the impact of America’s burgeoning defense industry on the Louisville economy. The Club welcomed orations on fascism in Germany, communism in Russia and the need for U.S. support of China against Japan. The impact of war on civilians was a frequent topic. On June 6, 1940, the Board voted $200 to Red Cross for War Relief, and applauded the RI convention’s vote of $50,000 for people suffering in the conflict.

When the United States entered World War II in December 1941, Rotarians took their places, as they had done a generation earlier, in all the ranks of useful service, through additional gifts of funds for the war’s needy, work with defense related agencies, and support for servicemen.

Rotarian Frank Rash served as State Director of Draft Boards; Joseph Rauch, chair of the International Service Committee, was a popular speaker on war-related topics throughout Kentucky and southern Indiana. Many Rotarians served in the military forces. In December 1945, at the Club’s official celebration of the war’s end, 21 Rotarians were recognized for service, including two, Dave Fairleigh and Arnold Griswold, who had served as well in World War I. Also recognized were 119 sons and 3 daughters of Rotarians, including two who lost their lives in the conflict.

The return of peace brought the revival of community work. Club members played important roles in building George Rogers Clark Park, increased support for underprivileged children and revitalized the loan program for students of modest means. More outreach in the 1950s included support for the Harelip and Cleft Palate Foundation, a fund drive for the Hagan Surgical Research Foundation, and an innovative partnership with the Louisville public schools to bring intensive science training to capable high school students.

In the mid-fifties, after Brown vs. Board of Education and the beginnings of school desegregation, the Club played a major role in establishing the California and Ormsby Avenue Boys Clubs. Louisville was then viewed as a national model for effective school integration. The Rotary Club of Louisville adopted the Boy’s Club initiative both to support African-American youth and commemorate the Golden Anniversary of Rotary International. It was an ambitious project funded in part from Club-sponsored vending machines in businesses owned or operated by Rotarians.

Another major initiative was the launch of Scout-O-Rama in 1957. Well into the early 2000s, this annual two-day event engaged over one hundred of our members, providing judges for competitive events with as many as 10,000 Scouts from throughout the state. Rotarians were the food concession workers and ticket takers and as well as the organizers of all behind the scenes activities.

The decade of the 1950s was also a time of change and growth for the Club. In 1953 the Club launched the Yearlings program, providing orientation and training for the surge in new members. In 1954-55 the Club officially adopted the Rotary International Constitution and the now ever-present Rotary Four-Way Test. The originator of the Test, RI President Herbert J. Taylor, spoke at the Club in 1955, prompting the creation of a Four-Way Test Committee which added energy to a host of new and reimagined service projects.

One of these was a public effort to increase polio immunization; 50 members took their series of shots at weekly meetings. Other initiatives included a pledge of $7,200 to the state-wide Rotary Lodge project at Camp KYSOC, the Easterseals treatment center in Carrollton, and the completion of the new Boys Club on Ormsby Avenue.

By 1962, the 50th anniversary of the Rotary Club of Louisville, membership had grown to 422, up 63% from 25 years earlier, and its commitment to service was stronger than ever.

1962-1987: Diversifying Membership, Searching for a Home, and Growing the Commitment to “Service Above Self”

The 1960s was a time of rising activism on civil rights in Louisville, beginning with the “Nothing New for Easter” demonstrations in 1960-61 and continuing through the Kentucky Civil Rights Act in 1965 and the open housing protests of 1968. The Rotary Club of Louisville, constrained in part by the Club Constitution’s ban on political statements, stayed above the fray. Club leadership occasionally addressed social welfare issues, including employment for youth coming out of the juvenile court system, fundraising for the Newburg Boys Club and a challenge from the city’s Health and Welfare Council urging Rotary to focus on public housing and black capitalism. But weekly meetings and Sparks issues barely touched matters of race and civil rights. That was the case at least until 1968 when individual Rotarians began a quiet push to diversify the membership.

The Club had long since dropped the “white adult male” membership stipulation in the original 1912 constitution. In April 1923, during the annual election-of-officers meeting, the Club unanimously adopted a new constitution with the generic “adult males of good character”” phrasing in Rotary International’s Standard Constitution. But it was not until 1968 and 1969 during the presidencies of J. Ed McConnell and James M. Rosenblum that recruiting African-Americans to membership became a priority. Club records show internal debate over particular candidates in June 1968, then on December 16 the unanimous election of Arthur M. Walters, the Executive Director of the Urban League. Sparks soon announced Art Walters as “our first new member of 1969.”

It was another four years before Milburn T. Maupin, the first African-American administrator in the central office of the Louisville city school system, became the Club’s second black member. From 1975 through 1979 the Louisville Club welcomed two additional black leaders: Wendell Rayburn, Dean of University College at the University of Louisville, and Bobby James Griffin, General Manager of the Transit Authority of the River City (TARC). By the Club’s 75th anniversary in 1987, aeronautical engineer Paul Hasty and businessman George N. King, Jr. also joined. But the total black membership at that point was three (including Arthur Walters), less than 1% of the 475 Rotarians on the rolls.

As significant as these tentative first steps toward diversity were, the Rotary Club of Louisville’s third quarter-century will be remembered more as a time of constant search for new meeting places. For 47 years the Brown Hotel had served as the Club’s home base. But that gracious venue closed in 1971 following the death of its founder, J. Graham Brown.

As past president Joseph Lenihan remembered it, “the Club was given but 30 days to find a new home. Cat-like the Club landed on its feet, took off on a dead run, and promptly found a new home at the Kentucky Hotel at what was then Fourth and Walnut Street. But its wandering had just begun.”

When Club leaders heard rumors about the imminent sale of the Kentucky Hotel, President James Tate formed a special committee to find a more permanent meeting place. Over the next five months, the committee explored 20 possible locations. Many were downtown like the Seelbach Hotel, the Bank of Louisville building and the soon-to-open Galt House, whose owner Al J. Schneider declared “no interest in housing Rotary.” Some locations were as far south as the Fair and Exposition Center and the Executive Inn-Fairgrounds and as far north as the Marriott Inn in Clarksville, Indiana.

By October the Club had settled on a near suburban location: the new Holiday Inn-Rivermont at Zorn Avenue near the I-71 exit. The venue was more costly than the Brown, forcing leadership to increase dues from $80 to $95 a year. But the ample free parking and the prospect of a long-term arrangement sealed the decision. The Club held its first meeting on Zorn Avenue on November 26, 1971, and continued there for ten highly productive years.

Meetings during these “years of wandering” were both substantive and entertaining, highlighted by Carol Channing in 1962-63, two Governors of Kentucky, both the Commonwealth’s U.S. Senators, a Justice of the Kentucky Supreme Court, and the sports commentator Howard Cosell just before Derby.

On April 3rd, 1974, the day of Louisville’s tornado, Rotary International President Bill Carter of London, England was in town for a visit. According to Lenihan “[t]hose who had luncheon with him at the L&N guesthouse on Murphy Lane recall that a gust of wind almost tore the storm door off the hinges as he left and, for good reason, many missed the dinner that night at the Holiday Inn on Fern Valley Road.” The 1974 tornado was especially devastating in east Louisville where many Rotarians lived. Past President Martin Schmidt, who then served as Librarian at the Filson Historical Society, invited his fellow Rotarians to write out their experiences and submit them to the Filson for permanent keeping.

On June 25, 1981, the Club moved once more, this time to Jim Porter’s Tavern at the corner of Grinstead Drive and Lexington Road. Board minutes and Sparks faithfully referred to the new location as Jim Porter’s Restaurant but members understood their weekly luncheons occurred at one of Louisville’s most popular watering holes. The Club office relocated downtown to 824 South 4th Street, briefly complicating Club operations, and the slow service at the first Jim Porter’s meal tried the patience of the 292 attendees. By the second meeting, new President Gene Gardner had things “under control” and the Club settled in for a memorable 15 month stay.

In November 1982, the Club returned downtown to the YWCA (formerly the Henry Clay Hotel), and then in May 1985 came full circle to the refurbished Brown Hotel and its spacious Crystal Ballroom. On July 24th, 1987, the Ballroom was the site of the Club’s 75th anniversary celebration, with several hundred members and guests in attendance.

True to the spirit of “service above self,” the program at the celebration showcased an impressive array of community projects, including the student loan program, which in some years made as many as 50 loans a year to worthy students in total amounts as high as $35,000. (The loan fund reached a total value of $115,000 before changing circumstances led to its cancellation in the mid-1970s.) A host of new and ongoing projects included a stockade and bath house for the Rough River Boy Scout reservation; help for the Newburg Boys Club, the distribution of safe driving pamphlets about the then-new expressway system, and improvements at Plymouth Settlement House. Other projects provided assistance to the Burn Unit at Children’s Hospital, support for Camp Green Shores for children with disabilities, and the establishment of the Dental Care Homebound Program. The Club’s growing list of international initiatives included the Gift of Life heart surgery project for children from third world countries, and in 1987, a record donation of $137,000 to the Rotary International program to eliminate polio worldwide. These projects were funded in several ways, including weekly raffles of donated prizes, earnings from the Student Loan Fund, and the generosity of Club members.

Another point of service and celebration in the Crystal Ballroom was the growth of the Paul Harris Fellows program. In 1975 Howard Fitch was recognized as the club’s first Paul Harris Fellow for his gift to the Rotary International Foundation. By 1987, 50 Rotarians, including family members and friends, had achieved Fellows status.

The ebb and flow of the Club’s membership and weekly attendance in these years was notable. Membership grew from 423 in 1962 to a peak of 504 in 1981, leveled to 450 in the mid-1980s, but then dropped to the 340s at the time of the 75th anniversary. Attendance at weekly meetings remained a concern, reaching 84.65% of the total membership in 1968-69, but declining incrementally to the 74 to 79% range in the mid-1980s. At each board meeting, Club leaders addressed attendance issues, providing leaves of absence for those who were traveling or ill, making tough decisions about with what to do with members whose attendance had dropped below the expected 60%. Sparks always contained detailed lists of Louisville members who had fulfilled attendance obligations at other Clubs.

“Seven Decades Overdue”: Women Admitted to Membership

In January 1987 and continuing through the spring, RCL leaders closely followed a case before the U.S. Supreme Court about a dispute between Rotary International and a Rotary Club in Duarte, California. The issue: RI’s longstanding prohibition of women in membership. There were several attempts over the years, in Northern Ireland, England and India as well as the U.S., to admit women to membership, and women’s auxiliary groups like the Inner Wheel and Rotary-Anns had spread rapidly. But RI’s stance against full membership for women did not waiver. In 1977, when the Duarte Club admitted three women to membership, RI revoked the Club’s charter. The Club then sued, arguing that California’s civil rights laws prohibited discrimination by business-oriented clubs, and that led to 10 years of litigation through the state and federal courts.

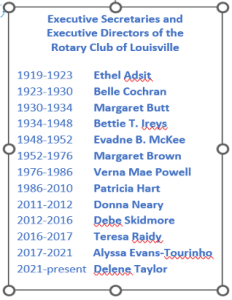

Throughout the history of the Louisville Club, women had played key roles, serving as office managers and executive directors every year since 1919 when the first permanent Rotary office opening in the lobby of the Watterson Hotel. From the beginning Club leaders took pride in the success of “Women of Rotary” events, recruited prominent women writers, educators and business leaders as speakers, and occasionally sponsored joint meetings with Louisville Women’s Clubs. The success of every social event and many service projects depended on the leadership

Throughout the history of the Louisville Club, women had played key roles, serving as office managers and executive directors every year since 1919 when the first permanent Rotary office opening in the lobby of the Watterson Hotel. From the beginning Club leaders took pride in the success of “Women of Rotary” events, recruited prominent women writers, educators and business leaders as speakers, and occasionally sponsored joint meetings with Louisville Women’s Clubs. The success of every social event and many service projects depended on the leadership

and expertise of women, who by the 1930s were routinely recognized in Board minutes and Sparks as “Rotary-Anns.” And yet seven and one-half decades after the founding in 1912, the Rotary Club of Louisville, like those throughout the US, remained all-male.

The Supreme Court’s decision in the California case changed that. On May 4, 1987, the Court ruled that states could outlaw sex discrimination by all-male business-oriented service clubs like Rotary. Although Kentucky’s public accommodations laws exempted private clubs, and although RI’s Constitution did not reflect the change until 1989, the Louisville Club proactively began to admit women.

At the 75th anniversary celebration, Patricia Hart, then serving as the Club’s Executive Director, received a standing ovation when introduced as the Louisville Club’s first female member. In October 1987, the Membership Committee recommended to the Board that the Club “actively pursue qualified women for membership.” Over the next two years, Board minutes, Sparks issues, and Club directories reflected the admission of seven additional female community and business leaders: Barbara Hoffman, Owner/President of a management consulting firm; Marie Humphries, Owner/President of a health services consulting company; Tommie O’Callaghan, president of O’Callaghan’s catering service; Joyce Seymour, Executive Director of the Kentuckiana Girl Scout Council; Justine Speer, Dean of the University of Louisville School of Nursing; Stephanie Speigel, Executive Director of Jewish Family and Vocational Services, and Gayle Walters Warren, Executive Director of the Leadership Louisville Foundation.

At the 75th anniversary celebration, Patricia Hart, then serving as the Club’s Executive Director, received a standing ovation when introduced as the Louisville Club’s first female member. In October 1987, the Membership Committee recommended to the Board that the Club “actively pursue qualified women for membership.” Over the next two years, Board minutes, Sparks issues, and Club directories reflected the admission of seven additional female community and business leaders: Barbara Hoffman, Owner/President of a management consulting firm; Marie Humphries, Owner/President of a health services consulting company; Tommie O’Callaghan, president of O’Callaghan’s catering service; Joyce Seymour, Executive Director of the Kentuckiana Girl Scout Council; Justine Speer, Dean of the University of Louisville School of Nursing; Stephanie Speigel, Executive Director of Jewish Family and Vocational Services, and Gayle Walters Warren, Executive Director of the Leadership Louisville Foundation.

The Galt House Era Begins

In early 1988, the regular meeting place relocated to the Galt House Hotel complex and the club’s office moved to One Riverfront Plaza. The Galt House would serve as home base for nearly twenty years. But to vary the routine, Club meetings sometimes occurred in venues outside the hotel, such as Actors Theatre, The Star of Louisville, Churchill Downs, The IMAX Theatre, Youth Performing Arts School, the Seelbach Hotel, The Louisville Zoo and The Cathedral of the Assumption.

In 1990 the long-range planning committee developed 38 proposed improvements in current activities including new approaches to recruiting and retaining members, providing information to members, and in-club recognition. The Club also committed itself to a more intentional philanthropy, dedicating a major portion of Dr. Bert Williams’ legacy gift of $844,000 for Rotary International to provide Paul Harris Fellow Awards to the club’s members. Nearly 200 Rotarians received the Fellows designation courtesy of the Williams legacy. By the turn of the 21st century, the Club would have nearly 250 Paul Harris Fellows, including family members and friends whom club members honored by making a Fellow gift. In 1999, Theodore Buerck provided over $600,000 to the Rotary International Foundation and another $600,000 to the Club’s own Louisville Rotary Foundation. Rotarian E. Randall Allen bequeathed the sum of $577,000 to the Rotary Foundation of Rotary International.

In 1992 the Club released some of its assigned territory to help organize a Rotary Club in Fern Creek, and again in 1995 for creation of a new club in Prospect. These were the eighth and ninth new clubs to be formed in the Louisville metropolitan area since the original territory was designated for the Louisville Club in 1912.

The New Century and New Dimensions of “Service Above Self”

In the late 1990s, with the new millennium in sight, the Rotary Club of Louisville stepped up its commitments in two key areas: international partnerships and the development of a broader, more diverse membership base and leadership group.

For many years the Club’s International Service Committee had sponsored the International Scholarship Competition and the Kentucky Youth Scholarship Exchange. In 1996, the Club moved aggressively into international work, joining Rotary International’s Saving Lives Worldwide initiative to collect and distribute surplus medical supplies and equipment to the world’s poorest communities. Over the next eight years, Louisville Rotarians contributed to 17 major shipments valued at $4 million to hospitals and rural clinics in Romania, Latvia, Nicaragua, Ukraine, Panama, Ecuador, Ghana, Barbados, Belize and Nepal. The Louisville Club partnered with Rotary clubs in Cincinnati and Kathmandu to establish a “first of its kind” pediatric dialysis clinic in rural Nepal, and joined in a multi-Club effort to setup and sustain dental clinics in Panama, Ecuador and Nepal and water projects in West Africa. Throughout these years, the Club continued its substantial contributions to Rotary International’s PolioPlus campaign to eradicate the disease across the globe.

Also in 1996, the Club launched the Rotary Leadership Fellows Program which each year identified a diverse group of early-career community leaders in a formal, three-year Rotary leadership development program. The Club recruited candidates from the MBA program at the University of Louisville’s College of Business and Public Administration. From the inception, the majority were women, several of whom joined the club and later assumed leadership positions. In 1998, eleven years after Patricia Hart became the Club’s first female member, Merrily Orsini was elected as the Club’s first president. From that point forward, women in membership grew, albeit slowly, reaching 14 percent of total club membership by 2012, the year of Club’s 100th anniversary celebration.

“Service Above Self,” along with the volunteer effort and fundraising the phrase had come to symbolize, continued to be a major emphasis in the first decade of the 21st century. In 2000, to cite one example, club members joined the campaign for the Home for the Innocents, the 120 year old sanctuary and treatment facility for neglected and at-risk children which was then in the process of moving from overcrowded facilities on East Chestnut to an expansive new campus on Market Street. Gordon Brown, Executive Director of the Home and an active Rotarian, advocated forcefully for the expansion of clinical treatment, crisis intervention, foster care and adoption services. On October 28, 2000, in the Grand Ballroom of the Galt House, the Club hosted “a very special evening” with dinner, a car raffle and silent and live auctions. The event helped raise $250,000, contributing significantly to building the fully accessible playground and the Rotary House (later the Cralle Day House) on the new campus.

Another major commitment was the ‘Everyone Reads Program’, a community-wide effort to increase literacy rates in JCPS schools. Launched in 2004 during President Wayne Perkey’s year and continuing during Mike Kull’s presidency through 2006, nearly 100% of Rotarians volunteered or contributed to help JCPS students improve their reading skills. Other local efforts included the Party for DePaul (an annual fundraiser to support young people with learning differences), the massive Scout-o-Rama gatherings at Churchill Downs, Salvation Army bellringing during the holiday, the annual Unsung Hero Recognitions for all Jefferson County high schools, and numerous Habitat for Humanity building projects.

The first years of the new century also saw two major innovations in the Club’s commitment to philanthropy. One was the establishment of The 1912 Society which recognizes individuals whose estate planning includes a bequest to the Rotary Club of Louisville to support programs for disadvantaged residents. A second development was the expansion and reinvention of the Rotary Fund of Louisville, now supported by donations across the entire membership and devoted to projects local as well as international in scope, thereby complementing the work of RI’s Rotary Foundation. By 2009, the 1912 Society and the Rotary Fund of Louisville had increased the Club’s annual charitable grants from $12,000 to $98,000. By the centennial celebration of 2012, the Club’s endowment had grown to $1,750,000, providing a stable basis for the Club’s ongoing philanthropy. In 2014, President Greg Braun undertook a study of Club giving over the last 60 years, documenting that since 1954 the Club had invested $2,108,582 million in more than 100 separate projects.

The 100th Anniversary Signature Project

But the seeds for the Club’s most ambitious fundraising and service initiative were sown in 2010 when President Henry Heuser Jr., anticipating the upcoming centennial of the club’s founding, challenged his fellow Rotarians to launch an ambitious Signature Project called the Rotary Promise Scholarship. The idea was to create an endowment whose proceeds would provide last dollar scholarships to the graduates of selected Jefferson County high schools with large percentages of disadvantaged students. Over the next two years, Heuser and his fellow Rotarians quietly laid the groundwork for the project, working behind the scenes with potential donors and education partners.

In June, 2012, Club President Stet Stettin published an op-ed in the Courier-Journal announcing the goal to raise $2 million to establish a permanent endowment to support and sustain the effort. “By eliminating the cost of tuition as a barrier to college,” Dr. Stettin explained, “we hope to motivate students to be successful in high school and prepare for a higher education. We also want to make attending college an expectation, not an afterthought, for the students and their parents.”

On July 21, 2012 at the Ice House in Downtown Louisville, more than 650 Rotarians and guests attended the Club’s Centennial Celebration where President Stuart Alexander, the Club’s 100th president, confirmed the commitment to the endowment. In four successive years, the Club would raise $250,000, matched dollar for dollar by the Kentucky Community and Technical College System, to reach the $2 million goal. In 2016, graduates of Western High School and in 2017 Iroquois High School received the first scholarships to attend Jefferson Community and Technical College. After two years at JCTC, many would transfer to Promise Scholarship partner institutions like the University of Louisville or Indiana University Southeast.

Alongside the scholarships, Rotarians led by Walt Kunau created a mentoring program which engaged students at both high schools in focused academic and career planning. In short order, scores of Rotarians were contributing hundreds of hours to small group coaching sessions, engaging promising junior and seniors in deep discussions of goal setting and life and business skills.

The 100th anniversary also brought attention to areas where progress had been less than spectacular. Past President James U. Smith’s letter in the event program celebrated the Club’s last 25 years of “service above self” but then raised a serious concern about the diversity of the Club’s membership and leadership.

“This review would not do proper service or accurately reflect our past quarter century if it failed to mention the most important change in Rotary in its history. In 1987, [women] were admitted to Rotary. In that time, female participation in our Club has expanded to its present level of 14%. Sadly, in this 25 year period only one woman has been elected President of our Club. That must change. If the Rotary Club of Louisville is to remain relevant to all segments of our community we must embrace true and absolute parity among our members.”

Past President Smith then cited the Four Way Test, and asked “Do we as a Club pass that test? If not, then do we fail?”

Over the next eight years, the Club stepped up its recruitment of women. In 2016, Alice Bridges took the reins of leadership, and included membership growth and diversification among her major goals.

By 2018, 24% of the Club’s 431 members were women, a figure which exceeded the 22% figure for Rotary membership world-wide but fell short of the 32% number for the United States and 29% for District 6710. By 2020, when Julie Schmidt became the Club’s 3rd woman president, 26% of the members were women, a figure that would hold steady through 2021-22 when Jean West Losovio became the Club’s fourth female and first African-American president.

Responding to the Challenges of Covid 19 and Civil Unrest

In 2020-21, when the Covid 19 pandemic and the protests over the death of Breonna Taylor rocked the Louisville community, a time when only 25 of the club’s 377 members were African-American or other underrepresented minorities, the Club turned its attention to issues of fairness and equity, including the recruitment of a more diverse and inclusive membership.

Covid 19 shut down in-person meetings on March 19, 2020. President Luke Schmidt and the Club quickly went virtual, maintaining a full schedule and continuing to serve, even in the midst of the pandemic, as Louisville’s premier weekly platform for speakers and issues. Naturally Covid 19 and its impact was a major theme, beginning in April with Dr. Michael Saag, a leading epidemiologist and Covid survivor who offered a unique perspective on the escalating public health crisis. Racial justice was a second major emphasis through the year, starting in July with Metro Council President David James and ACLU representative Katurah Herron on the causes of civil unrest in the city.

Covid 19 shut down in-person meetings on March 19, 2020. President Luke Schmidt and the Club quickly went virtual, maintaining a full schedule and continuing to serve, even in the midst of the pandemic, as Louisville’s premier weekly platform for speakers and issues. Naturally Covid 19 and its impact was a major theme, beginning in April with Dr. Michael Saag, a leading epidemiologist and Covid survivor who offered a unique perspective on the escalating public health crisis. Racial justice was a second major emphasis through the year, starting in July with Metro Council President David James and ACLU representative Katurah Herron on the causes of civil unrest in the city.

Under President Julie Schmidt’s leadership, the Club continued to host high profile leaders, including the presidents of the University of Louisville and the University of Kentucky as well Kentucky’s senior U.S. Senator and his Democratic challenger. Several of Kentucky’s constitutional officers graced the stage, including the Secretary of Agriculture, Secretary of State, and Attorney General, as did the Speaker of the Kentucky House of Representatives and Louisville’s eight-term Representative to Congress. Mayor Greg Fischer’s annual State of the City address in January drew an audience of more than 220, as did Governor Andy Beshear’s talk in May to a joint meeting of the Louisville and Lexington Rotary clubs.

Entrepreneurs and business leaders featured prominently throughout 2020-21 including Toyota of Kentucky President Susan Elkington and Jonathan Webb, founder and CEO of AppHarvest, Mike Jones, CFO of UPS, and Kevin Nolan, President and CEO of GE Appliances. Each week, prior to the main speaker, the Club hosted “Pre-Meeting Conversations” with the Club’s own leaders (like Barbara Jamison, CEO of the Kentucky Opera). A special schedule of Business Synergy events, held once a month during the evenings, showcased topics as various as “Salvador Dali: the Brilliant and Bizarre Surrealist” and “OCEARCH: A Lifelong Study of the White Shark.”

During these months the Club increased its commitment to “service above self,” contributing $25,000 to the Community Foundation of Louisville’s COVID-19 Response Fund to assist those negatively impacted by the economic downturn. The Club continued to serve meals and provide support to homeless men at the ReCenter Ministeries-Life Change program and again joined the community-wide fight against labor trafficking, providing volunteer leadership and substantial funding for the annual UN Human Rights Day conference.

In the midst of the pandemic, the Club joined with Lexington Rotary and RI to provide septic systems and clean water to households in rural southeastern Kentucky, and it carried through with ongoing international commitments, landing a $35,000 Rotary International grant to provide purification and pumping systems for safe drinking water in Uganda and investing more than $10,000 to water and sanitation projects in El Salvador and Guatemala. Just one year prior, the Rotary Fund of Louisville provided $15,000 to potable water installations in the two Central American countries, an additional $16,000 to sanitation projects in Uganda and Kenya and $5000 for diagnostic equipment for a Children’s Cancer Clinic in Montevideo, Uruguay. The Club also contributed $7,500 to help Mayan women in the mountains of Guatemala learn to install and maintain solar lighting, enabling their children to do homework at night.

While the in-person mentoring sessions at Western and Iroquois high schools all but shutdown during 2020-21, continuing in limited form with the WHS Early College group, the Club maintained its commitment to the Rotary Promise Scholarship enterprise. Rotarians Ken Middleton and Kevin Wardell had just redesigned the scholarship program to align with the community-wide Evolve502 initiative, renaming it the Rotary Honors Scholars Program, adding student achievement grants to encourage persistence and awarding innovation grants to institutions to promote educational attainment. In the fall of 2021, the mentoring program resumed at Western and Iroquois high schools and returned full force to the Early College program at JCTC-Southwest. By year’s end, a new Interact program was in place and 60 Rotarians and community volunteers had contributed hundreds of hours to the coaching sessions, engaging more than 150 students in meaningful discussions of academic success and career planning.

The Club contributed substantially to the West End School Literacy Curriculum and renovation of the playground at St. Benedict Early Childhood Center, as well as to the Education Justice program, matching high achieving students at Iroquois and Western high schools with middle schoolers in a life changing, long-term mentoring program. The Club also continued its decades long commitment to the Unsung Heroes program, providing recognition and scholarships to students in each high school (private and public) in the county.

Undoubtedly the most significant step forward during the spring and summer of 2020 was the Club’s reexamination of programs and plans related to diversity, equity and inclusion. At the beginning of his term in 2019, President Luke Schmidt had established a Community Impact Committee for the “sole purpose of identifying key issues and problems in Louisville and facilitating solutions to those problems.” The CIC’s initial goal was to find creative solutions to the graffiti problem on signs and underpasses, and its first project was construction of “the Louisville Knot,” a new cityscape art installation on Main Street, under the 9th Street overpass. The Louisville Knot symbolized our Club’s desire to eliminate the “Ninth Street Divide” between West Louisville and the community at large.

In the spring of 2020, at the height of the protests over the shooting of Breonna Taylor, President Luke asked the CIC “to give thoughtful consideration” to other ways RLC could address community issues. In August, after the gavel passed to President Julie Schmidt, CIC held two weekend retreats, hearing from speakers on issues of racism, equity and justice and exploring new avenues for “Service above Self,” all while maintaining the Club’s tradition of non-partisanship and political neutrality.

The result was the creation of five CIC action teams on internal issues, public safety, policies and justice, community needs, education and messaging and outreach. Over the next two years, the five groups advanced significant initiatives, including the first-ever Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) statement, a vendor equity policy, and a diversity-focused recruitment campaign to eliminate onerous telephone fees in the Metro Department of Corrections. Other CIC initiatives included a $10,000 grant to the West Louisville Hope and Wellness Clinic and an educational partnership with the NAACP to implement Junior Achievement’s 3DE program at Valley High School. A key result of these efforts was the creation of a permanent DEI committee, empowered to expand the work, led by a committed leader with a seat on the RCoL board.

The most ambitious project — one still in development in in September 2022 – is the West Louisville Housing Initiative, the Club’s next Signature Project, a first-in-the-nation effort to create a $5 million revolving loan fund for low- to moderate-income home buyers. The project addresses the residual effects of red lining in African-American neighborhoods, and will empower 63 families who are currently renters to qualify for loans, own a home and build generational wealth.

The years from 2020 through 2022, which encompassed the pandemic and civil unrest, presented extraordinary challenges to the Club, just as they did to the community as a whole. But as the torch of leadership passed from presidents Luke Schmidt to Julie Schmidt to Jean West Losovio to Walt Kunau, the Rotary Club of Louisville not only remained strong. It was well positioned – and driven by new energy and sense of purpose — to deliver on its stated mission “to provide a fellowship of inspired business, professional and civic leaders with exceptional opportunities for humanitarian and civic service, while promoting integrity, understanding and goodwill on a local, national and worldwide basis.”